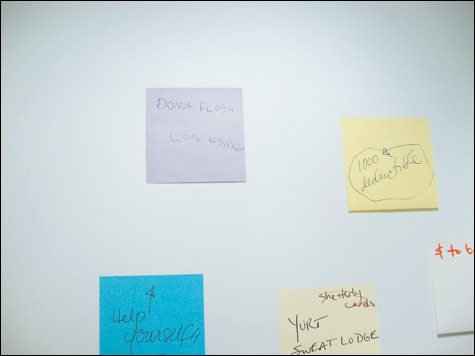

LOVE THE NOTES Adriane Herman's Post-its. |

The three artists whose work is currently on view at Whitney Art Works in Portland have a taste for narratives, real or invented. Melinda Barnes's little drawings document disconnected shards of apparently fictional lives. Tim Clorius projects contemporary ideas backward into an imagined earlier century. Adriane Herman gathers the fragmentary imperatives of real lives and weaves them into a wandering thread.

Herman's pieces consist of carefully executed reproductions of real Post-it notes that have been left as reminders or instructions. They appear in the show as sign-sized papers with the characteristic colors and curves of Post-it notes, their original casual messages carefully rendered by Herman's silkscreen process. You are instructed to help yourself or reminded to do small things like eat the cake (but not the sequin eyes), take money to the bank, or do homework. Some directives are more thoroughgoing: One should plan out days, pay off debt, or eat fruit. "I didn't know it was loaded" represents, I hope, a joke. One of my favorites is "Do not flosh Love esme" [sic]. It combines a cautionary imperative with a warm greeting.

Herman's work produces an embarrassingly voyeuristic feeling of violating someone's privacy. The imaginary narratives these pieces induce are just that, imaginary, but they are culled from the minutiae of real people's lives. I'll never forget to discard a Post-it again.

Tim Clorius makes his new paintings look old to add an extra layer of narrative to the theatrical content of their subject. Many of this group of 22 paintings look aged, as if their varnish had darkened and bits of paint had flaked off. The are mostly done in a style reminiscent of mid-19th century theater flats or Georgian genre painters. Some even have proscenium curtains framing the picture's action. In "Bright Future," for instance, green curtains enclose what appears to be an allegorical action involving a youth, a stag, and a lake.

The contrasting dynamic between the apparent age of the painting and the contemporary nature of the actual action is perhaps clearest in "Mail-Order-Bride, not what he Ordered," at two feet square the largest in the group. A man in vaguely Elizabethan dress with doublet, hose, and a lace collar, talks into a telephone. Beside him is a nude woman with cellophane crumpled around her feet, looking pensive. It is clear that he has opened his package and found it not what he expected and is contacting customer service.

Melinda Barnes shows 27 postcard-size drawings that appear to be depictions of little moments, the commonplace details of everyday existence, except they aren't. They may be quotidian, but they are also right on the borderline of surreal weirdness. It is as if Barnes had cut a little section of some much larger image that must remain unknown. She shows, for instance, the upper right corner of a recessed doorway that is decorated with a bit of fancy scrollwork. Only three letters on the door are showing, "nce." One assumes it means "entrance," but maybe not. The curious bit here is what the part that is missing, like Holmes's silent dog in the night. Since there is nothing there, what is the significance of this corner? Barnes has gone to a bit of trouble to present us with this fragment as a signifier of some hermetic objective.

Each of these drawings has, in its own way, the same sense of mysterious banality. A bald man is seen from the rear, an IV bag is vignetted against a brick wall, a piece of a map has too little information to be useful, an apparent label to a box of walnuts has the top third of the letters cut off. Barnes quietly but firmly directs our attention to the parts of the scene that are missing, are probably important, and are beyond what we can know.

Ken Greenleaf can be reached at ken.greenleaf@gmail.com.