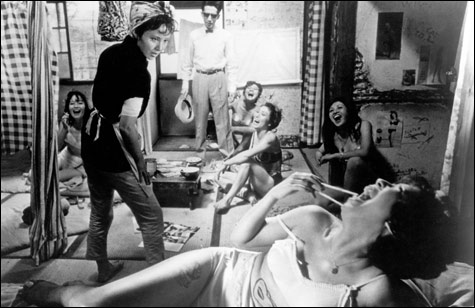

PIGS AND BATTLESHIPS: A battle between pigs for whatever slop there is. |

| “Vanishing Points: The Films of Shohei Imamura” | Harvard Film Archive: December 1-14 |

You can draw the time line of the Japanese new wave in scores of different ways — there were multiple possible launching points, and the big players evident in the ’50s and ’60s were young, old, and in between — but Shohei Imamura was an unarguably major, and quizzically ambiguous, figure in the landscape, an artiste among pulp mavens and a pop comic amid tragedians, a deep-dish cynic and a folksy absurdist. Dead last year at 79, the two-time Palme d’Or winner was one of the last of his slowly dying breed, survived still only by Seijun Suzuki, Kon Ichikawa, and Nagisa Oshima.He may have also been the least categorizable filmmaker of the lot (always a handicap in an auteurist world), careless with genre and frenzied about social critique. At the same time, it would be difficult to mistake an Imamura film for anyone else’s — few filmmakers ever had a more dire view of mankind. His was rooted to the verities of Japanese life in extremis. His characters are rarely more than a few stealthy crawl paces away from homicidal jungle law and pig-sty madness. The son of a doctor, he began as a studio apprentice with Yasujiro Ozu, and he quickly established a distaste for his sensei’s restraint and quiet eloquence. (Even Imamura’s interior spaces — always an æsthetic priority in Japan — are deliberately cramped and chaotic, in direct contrast to Ozu’s famous, measured rooms.) In fact, he has always seemed a sort of Japanese Sam Fuller, fascinated with working-class ruin and primal impulse. And he could be viciously funny — which alone set him apart from most of his industry’s big guns. His first phase, beginning in 1958, was taken up with racy comedies and melodramas, but it wasn’t till PIGS AND BATTLESHIPS (1961; December 8 at 7 pm) that he became, immediately, an internationally known voice. A defining self-portrait of Japan in the post-war moment, the film visits a virtual war zone of threadbare urban iniquity, a Japanese coastal city in which everyone is either a whore or a pimp, where emergent gangs kill each other over the right to control the black market in US Army food scraps, where capitalism isn’t even predation or victimization but a battle between pigs for whatever slop there is. It’s a cruelly comic movie (with a gangster’s corpse that keeps needing to be redisposed of), for the most part, because of Imamura’s domineering, amused disdain for his subjects — here was Japan’s incarnation of Buñuel, omnisciently satiric and utterly cynical, if not as graceful and subtle, and lasering through the Buñuelian derision for hypocrisy (religious, social, sexual, etc.) to hit the raw bone of untempered lust and hunger.

Related

Related:

Blu Christmas . . . without DVD, In the realm of Oshima, Fissionable material, More

- Blu Christmas . . . without DVD

Ah, yes: the most wonderful time of the year, tinged with muddy snow and the creeping darkness of our most recent Depression.

- In the realm of Oshima

The HFA looks back at the bad boy of Japanese cinema

- Fissionable material

The Iranian masters upon whom we’ve come to depend seem for the moment to be indulging in their global fame.

- For kids of all ages

In this spineless age of ours, what more rueful sight than a child maneuvering his/her cowed parents to some insulting CGI movie?

- Fit to be Thai’d

This retro spoof is an affectionate homage to cheapo Thai Westerns of the 1950s, trashy Thai action films of the 1960s, weepie melodramas of all eras.

- Thelma and Marty do the Coolidge

It was hard to tell who was more excited about the presence of Martin Scorsese and Thelma Schoonmaker at the Coolidge Corner Theatre Thursday night.

- Film @ Noir

“It’s called The Wizard of Gore, it’s with the Suicide Girls in it. What did you fuckin’ expect?!”

- Crossword: ''The worst of 2007''

Let us look back, and feel shame.

- Legend of the last

They all start the same way.

- Dark new wave

Every now and then, it happens: a new wave from where?

- Adaptation

If your inner Mr. Memory — not to mention your outer Blockbuster — is operating, you recall The 39 Steps.

- Less

Topics

Topics:

Features

, Entertainment, Movies, U.S. Army, More  , Entertainment, Movies, U.S. Army, Entertainment Awards, Film Awards, Shohei Imamura, Yasujiro Ozu, Koji Yakusho, Nagisa Oshima, Less

, Entertainment, Movies, U.S. Army, Entertainment Awards, Film Awards, Shohei Imamura, Yasujiro Ozu, Koji Yakusho, Nagisa Oshima, Less