RABBIT AND ROGUE: In Twyla Tharp’s metaphysics, dancing can transform chaos into utopia. |

NEW YORK — Five minutes after the curtain came down on Twyla Tharp’s new ballet, Rabbit and Rogue, at the Metropolitan Opera House, a woman waiting for a bus was on the phone telling a friend to buy a ticket. “You have to see this!” she exclaimed. “This is the most phenomenal thing I’ve ever seen.” On the bus, another woman saw me looking over the program and asked what the story of the ballet was. Her friend thought it was an abstract ballet, and their discussion continued.

Next day the critics were savage, but it tells you something about a ballet when the audience leaves the theater with questions.

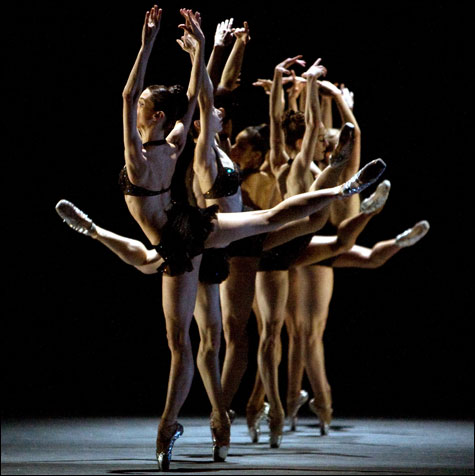

Tharp’s dances almost invariably have a euphoric effect on their first audiences, even when they miss their mark and don’t hold up over the long run. Rabbit and Rogue followed in the direction of her recent work, preserving the exhilarating, non-stop virtuosity she’s able to pull out of dancers, and sparking some speculation about “meaning” through her use of character devices.

Rabbit and Rogue, which premiered June 3 and ran for a week during American Ballet Theatre’s spring season at the Met, has two male leads, two secondary couples, a tertiary quartet, and a 12-member corps de ballet. It’s as formally structured as In the Upper Room or Tharp’s last ballet for ABT, Variations on a Themeby Haydn (2000), but it’s more than pure form. Tharp admitted in an interview that the leading men represent contrasting brothers, or the conflicting sides of one personality, but beyond that she wouldn’t elaborate on a private throughline that could encompass anything from dysfunctional families (hers, anyone’s) to cosmic evolution.

The surface of the ballet yields little help on that level, and though I might intuitively try to read her mind, during my one viewing I kept coming across a different set of markers. Early on, I realized that Danny Elfman’s gamelan-influenced score was insistently driving the dancers. The ceaseless momentum prevents you from being anything more than stunned, before the next stunning thing occurs. The whole stage seemed to be in perpetual motion, like a movie chase that never ends, only shifts camera locations.

Before the dance was done, I decided that Tharp was constructing the work with a movie editor’s technique, cutting back and forth from one set of characters to another. Each set plays its own role and sometimes interacts with the others, but what you pay attention to is the individual movement clusters, the dancing designs as they unfold. It’s like a TV serial, where three or four plot elements arise, break off, intersect, separate again, and maybe resolve, within an hour’s installment.

Rabbit and Rogue is never so literal, but Marcelo Gomes and Sascha Radetsky (I saw the second cast on Wednesday afternoon) seem to be genial antagonists, alternately punching each other out and facilitating each other’s phenomenal tricks. The other characters surge in and out like their aspirations and interrupted dreams.

In Tharp’s metaphysics, dancing can transform chaos (i.e., conflict, strife, opposing styles) into utopia (harmony, agreement, maturity). Always refashioned into new examples, this process keeps reappearing in her work, from Deuce Coupe (1973), the Tharp/Joffrey Ballet fusion work, to Push Comes to Shove (1976), her first ballet for ABT, and all the way to Movin’ Out (2002), the Broadway show.