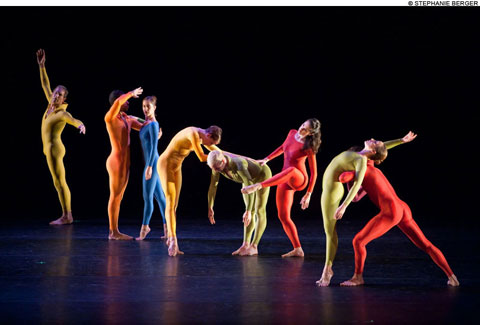

SECOND HAND The 10 dancers move in a mode of deranged ballet, balancing in untenable positions, tilting and arching with relaxed arms and pointed feet. |

NEW YORK — Expiring dance companies either implode from suppressed internal troubles, or they just peter out quietly. The Merce Cunningham Dance Company has chosen a different route. Before the choreographer died in the summer of 2009, he and his associates worked out a plan to terminate operations after two years of touring. Last week at Brooklyn Academy of Music we saw the penultimate hurrah. The company goes to Paris, then back to its home town for a New Year's finale at the Park Avenue Armory.

The whole process amounts to a prolonged and amply publicized farewell, a three-way tribute: to Cunningham himself, to his dedicated dancers, and to the repertory he created over 65 extraordinary years. Last week the company performed six of these dances for the last time. The dance world gathered. There were ovations and tears and, for me, renewed appreciation and bottomless regret.

PHOTOS: Merce Cunningham Dance Company

The Cunningham Trust has been established to oversee revivals of Cunningham's choreography on other dance companies, but they won't have the style or the psychic rapport of the marvelous 14-member ensemble that's about to disband. Cunningham employed everything from chance operations to computers so his work wouldn't become formulaic. I can imagine other dance companies mastering his technique, but what about the unpredictable sound scores or the last-minute ordering of steps that his dancers absorbed so coolly?

Cunningham dancers have a certain look. His vocabulary of movement emphasizes the legs and feet. There's relatively little embellishment in the arms and torso but a very detailed approach to space — a multidirectional differentiation of body parts, an acute sensitivity to where everyone else is, an appetite for traveling. But he could modulate this vocabulary for different dances.

Roaratorio (1983) is based on John Cage's "Irish Circus on Finnegans Wake," a soundscape of conversation, crying babies, rushing water, birds, flutes, drumming, the constant auditory jumble of any city. The dance isn't a story, but a jovial gathering, with very fast, eccentric footwork in the character of Irish step dancing, and playful duets, strolling couples, and a big, exuberant circle of jumping.

Much earlier, Second Hand (1970) borrowed simplicity and serenity from Cage's one-note piano variations on Erik Satie's "Socrate," and from the classical purity of Cunningham's muse, dancer Carolyn Brown. The 10 dancers move in a mode of deranged ballet, balancing in untenable positions, tilting and arching with relaxed arms and pointed feet. Robert Swinston, who's headed the company since Cunningham's death, danced the choreographer's role, looking uncannily like him.

The calm and spaciousness surfaced again in Pond Way (1998), where the dancers, in floaty white pajamas, sped and spun across the space like dragonflies. Sometimes they stood, stiff-legged on relevé, or spurted straight up in the air, or frog-jumped in and out. With Brian Eno's quiet score of low drones and bells, they evoked a scene of sunset stillness and splashes.

Cunningham loved nature. He drew carefully observed animals and choreographed them many times. In this series, only RainForest (1968) seemed to misfire. Replicas of Andy Warhol's mylar pillows took over the dance. These galumphing objects insisted on colonizing the floor and bouncing off the stage into the delighted audience. Cunningham's mysterious dancer-creatures couldn't compete with them.