CHILLING: Serena Perrone’s “A Day in November, Impending Loss.”

|

Gathering women artists together in a show is always at least a little problematic. Special categorizing risks condescending, like calling a female actor an actress. Years ago a Saturday Night Live sketch made the point devastatingly as an arch-eyebrowed John Lithgow led viewers through an art show of modern masters. The only common distinction noted? Each artist was, yet again, a man.“Voice: Women in Contemporary Art” is at the Providence Art Club in the large Maxwell Mays Gallery, making the possibly futile attempt to find commonality in sprawling diversity.

Perhaps the only thing that unarguably pulls together these sculptures, paintings, photographs, and drawings is that they all were appreciated through the sensibility of artist Kara Walker. She selected 29 works by 27 artists, eight of whom are from Rhode Island. As a RISD MFA grad and MacArthur Fellow, Walker has drawn attention locally, but her wider success is to the credit of her edgy subject matter: her black paper silhouette cutouts, or drawings simulating them, typically depict antebellum atrocities against slaves.

Knowing that there has been such a curatorial eye behind these selections is helpful. We can scan the gallery with wary attention, attuned to cautious takes on contemporary culture. Implied menace and vulnerability seeps to the foreground, such as in Whitney Hubbs’s untitled juxtaposition of two color photographs. In one a ragged yellow-orange ribbon flaps in a snowstorm, tied to a steel post; in the other a woman with hair that identical color holds a cigarette in her hand, obscuring her face.

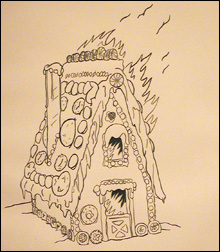

Serena Perrone’s “A Day in November, Impending Loss” is a chilling woodcut showing children in darkened woods looking way off to a house amidst light-flooded trees. Even more explicit a threat to children (or to any innocence still within us) are images from an untitled “series of drawings based on the effects of war” by Karen Kirchoff: a gingerbread house aflame, a mother protecting her children, bloody axe in hand, dead wolf at feet.

In the context of surrounding work, even the delicate pencil and watercolor drawings of Lisa Costanzo’s “Hunting Series” remind us more forcefully of the death implied by the title, though the dogs at the feet of figures in 16th- and 18th-century period dress are resting, not running down game. Similarly, in “Maya and the Crabs,” a black-and-white photograph by Iris Falck Donnelly, at first glance we’re seeing merely a young girl intently engaged. But then we notice the contrast between the inert menace of the three plates of boiled crabs that surround her and the child’s bare, tan-lined skin; her picking unsqueamishly at a shell makes this a quiet little feminist celebration.

Sometimes gender assumptions affect what we think we perceive. In Jessi Katz’s “We: Lean,” two rolls of carpeting foam are jammed side-by-side into a glass container, sticking out and bending over under the weight of a glass cover. Who you are and what you’ve experienced controls what gender you assign to the taller, plainer length leaning over the smaller, more complexly textured one.

INNOCENCE LOST: An untitled work by Karen Kirchoff.

|

But what if we knew nothing of who put this show together, or even that all the artists are women? What here suggests female, feminist — or feminine — point of view? Which might one guess were not done by a male artist? Heather Hart’s “Uzi Coozie: M16” comes to mind. Whether it is a crochet in the shape of an Uzi or a gun covered with yarn is unknowable by looking, an ambiguity I like. But such a stereotypical assumption is defeated by Tiffany Doran’s “Like Coin, the Tinsel Clink of Compliment,” where three Cadillac Eldorados, painted on gold leaf, celebrate a typical male esthetic. Would anyone suggest that women being more caring than men had anything to do with Laura Collela’s “A Man, a Corpse, and a Pile of Nickels,” in which a long strip of video still blow-ups hangs down to that pile of change? The effects of gang street shootings are gender-neutral.“Women in Contemporary Art”? Those invited to display their work in this exhibition are artists — pure and simple. Female artists don’t need any justification to be gathered together in a no-males-allowed show other than that men have historically dominated the art world. As these works demonstrate, objecting or whining about that fact has long ceased being worthy artistic subject matter. As these women show, it’s the what, not the wherefrom, that counts most.