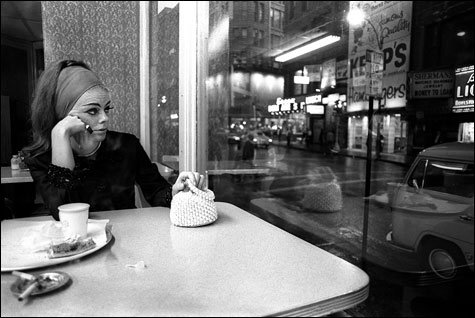

THE COMBAT ZONE, BOSTON, 1968 Berndt draws purpose out of blank stares and minor intimacies. |

Insight | Photos by Jerry Berndt; text by Maik Schluter, Felix Hoffmann, Susanne Holschbach, and Kathrin Peters | Steidl | 246 PAGES | $45 The Blue Room | Photos and notes by Eugene Richards | Phaidon Press | 168 pages | $100 |

A drunk in a cheap suit lies supine in an oily midnight alley. A young black woman in a mini-dress lands prone on a Boston sidewalk, surrounded by a ring of male legs. Two dirt-smudged baby dolls — one prone, the other supine — lie on a mildewed hemp carpet surrounded by chunks of crumbled wallboard in an abandoned house. One doll is covered with a toy blanket, as if she'd been put to bed just before something awful happened.It was a common Cold War–era obsession, this vicarious attraction to the apocalyptic dark side. It became a pat refutation of the unthreatened post-war reality we'd been promised but couldn't find — a reality manifested in existential poetry, social-realist movies, and various exercises in cultural slumming and gutter wallowing. The determinedly deluded dismissed it as downbeat posing. The willingly disillusioned called it reality, and they had proof — photo documentation that hope cannot be defined as pretending unpleasant things don't exist, that it instead involves accepting (not always to be confused with embracing) what is true as a circumstantial complexity, with the insignificance of all things as the bottom line.

But fatalism and depression are consequences of life, not goals. Cheer up and don't let this dust-to-dust business slow you down. That's something to keep in mind when confronting the work of Jerry Berndt and Eugene Richards, two photographers with Boston ties adept at making art from what a lot of people consider ugly, untouchable things.

Berndt (who, I'm proud to disclose, is a long-time friend and colleague) depicts isolation in crowded places with deserted night-time streetscapes, surreptitious shots taken in working-class bars, and unswept-sidewalk street photography. In his latest published collection, Richards, a Dorchester native and accomplished social-realist documentarian, abstracts the isolation theme with a series that amounts to photographing dreary ghosts in large-format color.

Jerry Berndt's Insight is a retrospective collection reaching back to some of this self-taught photographer's early self-assigned projects. The bulk of the work, which includes a late-'60s no-punches-pulled series shot in Boston's defunct Combat Zone, was recently exhibited, to effusive reviews, at C/O Berlin in the German capital. The book also features, in high-key color, a novel series of still-lifes based on the fanciful-to-disturbing dollhouse tableaux of Berndt's now-adult daughter, Emma, complete with Emma's explanatory captioning: "The babies are sleeping outside because there's a penguin in their house"; "Bad Bert was stealing babies, so I put him in jail and he can't come out." That's followed by a touchingly frank biographical series based on the death of Berndt's grandmother and a concluding essay on homelessness.